World War I

In 1917 it was decided to form Squadrons in Canada to be known as Canadian Reserve

Squadrons, a nucleus flight to be sent from England for each squadron. These

squadrons were to be known as Nos. 78 to 97 (Canadian) Reserve Squadrons. No. 93

had not been formed by the end of the war.

World War II - Churchill's Aerial Mines Project

No. 420 Flight formed on 29th September 1940, under the command of Flt. Lt. Burke for

the purpose of experimental work in connection with the use of aerial mines in

intercepting enemy planes. These experiments were carried out with Harrow aircraft

using Battle aircraft as targets. On 26th October 1940, the first practical experiment

took place against the enemy, one aircraft being probably destroyed.

On 7th December, 1940 this Flight became No. 93 Squadron under the command of Wing

Commander J.W. Homer. It consisted of 2 Havoc Flights and 1 Wellington Flight.

Experiments continued and on 23rd April 1941 the 2 Havoc Flights became operational on

night interception duties using mines and the third flight was taken to form the Fighter

Experimental Establishment.

Wing Commander M. B. Hamilton assumed Command on 23rd April, 1941.

During the following months the Squadron flew numerous operational sorties from

Middle Wallop with detachments operating at various times from Coltishall, Hibaldston

and Exeter. There is no record of any enemy aircraft destroyed during this period and

towards the end of the summer few operational sorties could be made owing to (i) the

absence of enemy aircraft and (ii) the presence of friendly aircraft.

At the end of November 1941 a decision was taken to discontinue the use of aerial mines in

night interception and as a result of this decision No. 93 Squadron was disbanded on

6th December, 1941.

Extracts from an AEROPLANE Magazine article "Clipping the Eagle's

Wings" by Dr Alfred Price published in the August 2006 Edition.

The Long Aerial Mine (LAM)

This entered service towards the end of 1940. The background to this weapon

is interesting. Before the war, tactical papers had often exaggerated

the danger to conventional fighters of attacking bomber formations.

It was argued that the defensive crossfire from 20 or more bombers in close

formation might inflict heavy losses on the interceptors.

Therefore it was important to devise a method of breaking-up bomber formations,

to allow the fighters to pick off the bombers individually. One proposed

method was to lay a defensive minefield. A line of such mines, positioned

across the path of an enemy bomber formation, would certainly cause it to break up.

Following much experimentation, the optimum configuration for the mine was determined.

The resulting weapon fitted into a cylindrical container 14in long and 7in in diameter,

and weighed 141b. After release from the aircraft the obstacle deployed.

It comprised, from top to bottom: a supporting parachute, a length of shock-absorber

cord, the cylindrical container, an AAD bomb, 2,000ft of piano wire and, at the bottom,

a second furled parachute.

When an aircraft struck the piano wire the shock wave ran up the wire, causing a weak

link to break, releasing the main supporting parachute and the cylindrical container.

As the container fell away the bomb was armed and a small stabilising parachute

connected to the weapon was released. Simultaneously, the shockwave travelled down

the piano wire and caused the lower parachute to open. This took up a position

behind the aircraft and pulled the bomb smartly down on the aircraft.

In the event, the Long Aerial Mine (LAM) was not ready for operations in time for

the Battle of Britain. However, in autumn 1940 Fighter Command's most difficult

problem became how to counter the night raider. The long-term answer was the

Bristol Beaufighter fitted with airborne interception (AI) radar, directed on to

its prey by a ground-controlled interception (GCI) precision radar. But each of

those systems was in an early state of development, and some time would elapse

before they were available in quantity. In the meantime, anything even remotely

likely to be effective against the night bombers was pressed into use, including

the Long Aerial Mine. German bombers attacking at night did not fly in

formation. Instead, they approached their targets at irregular intervals,

following their radio beams. At night, the mines were to serve a different

purpose than that originally proposed. Instead of being used to split up an

enemy formation, a line of mines would serve as an "aircraft trap" to destroy

bombers.

The minelaying task did not require an aircraft with particularly high performance.

The machine selected was the obsolete Handley Page Harrow twin-engined bomber.

Fully laden, its maximum speed was 170 m.p.h. at 20,000ft, and it took all of 46 min

to reach that altitude. The Harrow was modified to carry 120 Long Aerial Mines

weighing nearly 1,7001b. For night operations the spacing between individual mines

was 200ft, so the Harrow's complement would produce a curtain of danger 4½ miles long

and 2,000ft deep. The individual mines descended at about 1,000ft/min, so the

curtain remained effective for about 2 min.

In September 1940 No 420 Flight formed at Middle Wallop with modified Harrows.

During December 1940 the Flight was expanded into 93 Sqn and the new weapon was sent

into action. For these operations the Harrow was guided by ground radar to a

release position in front of the raiders. On the night of December 22 1940, Fit Lt P.L.

Burke laid out a line of mines in front of two enemy bombers. Shortly afterwards

one of the radar "blips" seemed suddenly to disappear from the screen, and the bomber

was assessed as "probably destroyed".

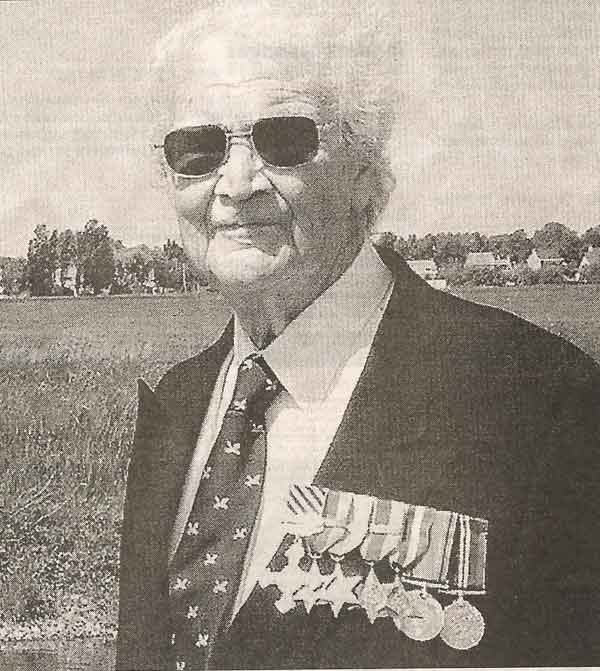

One of those who flew Harrows with 93 Sqn during the Long Aerial Mine operations was

Flt Lt Dennis Hayley-Bell. He later told the writer:

"One flew alone in the Harrow, which meant that during the long climb to height and

the subsequent wait for the enemy one felt rather lonely. The clumsy Harrow was not

an ideal machine to go to war in. It was very slow and, because there was no heating

and the cockpit sealing was often poor, very cold at high altitude. When the radar

controller saw a likely-looking enemy bomber coming in my direction, he would direct me

on to an intercept heading to one side and about 1,000ft above the intended victim.

At the critical moment I would receive the order to turn sharp left or right, so as to

bring me across the path of the victim. Then I would start the 'Mickey Mouse' the

clockwork unit which released the bombs - at the correct time intervals (just under 1 sec)

so they were strung out at 200ft intervals behind the aircraft. It took about 1½min

to drop one's complement of mines, then it was just a question of waiting. If one was

very lucky, one might see a flash to indicate that an enemy aircraft had hit one of the

wires and dragged down the bomb. But usually there was nothing to be seen. The mines

were always released some way out to sea, because any coming down on land might cause

damage. During one of the early operations the ground controller failed to make

sufficient allowance for the wind, with the result that several mines landed near

Bournemouth and the long wires shorted out overhead power lines in the area.

Fortunately everyone blamed the resultant power cuts on the Germans, so we escaped any

awkward questions."

Hayley-Bell's only successful mining operation was on the evening of March 13, 1941,

as German bombers came across the coast to attack Liverpool, Hull and Glasgow.

After taking off from Middle Wallop in a Harrow, he climbed to 17,000ft. Directed

by the radar station at Sopley, near Christchurch, he was positioned about four miles

ahead of and 3,000ft above an incoming bomber. At a point 12 miles off the coast near

Swanage he was ordered to begin releasing the mines. After a short wait he saw a

small explosion below him, followed by a much larger detonation, powerful enough to

shake the Harrow. Radar operators on the ground observed that the intended victim

had missed the minefield, but it appeared that another bomber in the area had picked

up a mine. Hayley-Bell was credited with one enemy aircraft destroyed.

Between March 11 and July 29, 1941, 93 Sqn flew a total of 112 minelaying sorties, and

in the course of these its aircraft attempted 59 interceptions. Of those, only 16

were sufficiently promising to warrant the laying of a minefield. The outcome was one

enemy bomber (Hayley-Bell's) claimed "destroyed" and three more "probably destroyed".

During the summer of 1941 the German night raids tapered off, and by then the Beaufighter

was in service in useful numbers. Compared with that, the Long Aerial Mine gave only

a very low probability of a kill, and operations with the weapon ceased in October 1941.

[End of Aeroplane Article. Thanks to Aeroplane and Dr Alfred Price.]

World War II - Disbandment from December 1941

to June 1942

Spitfires on Convoy Protection

RN light cruisers HMS Argonaut with Spitfire RAF 93Sqn HNA flying overhead - 1st Aug 1942.

(Thanks to Matthew Acred and The Imperial War Museum.)

The Squadron was reformed at Andress, Isle of Man on 1st June 1942 as a fighter squadron

equipped with Spitfires, beginning its operational flying on 10th July, with a convoy

escort patrol. Then followed many such patrols as well as scrambles and shipping

protection patrols until 8th September 1942 when the squadron moved to Wansford, Northants.

North Africa

No operations were flown from Wansford as the squadron was preparing for service

overseas its destination being North Africa. Sixteen aircraft were flown out by pilots

arriving at Maison Blanche on 13th November 1942 and on 21st November 1942 were flown to

Souk-el-Arba commencing operations in support of forward troops. The ground party

arrived at Algiers on 22nd November 1942 and proceeded to Souk-el-Arba arriving there on

7th December 1942.

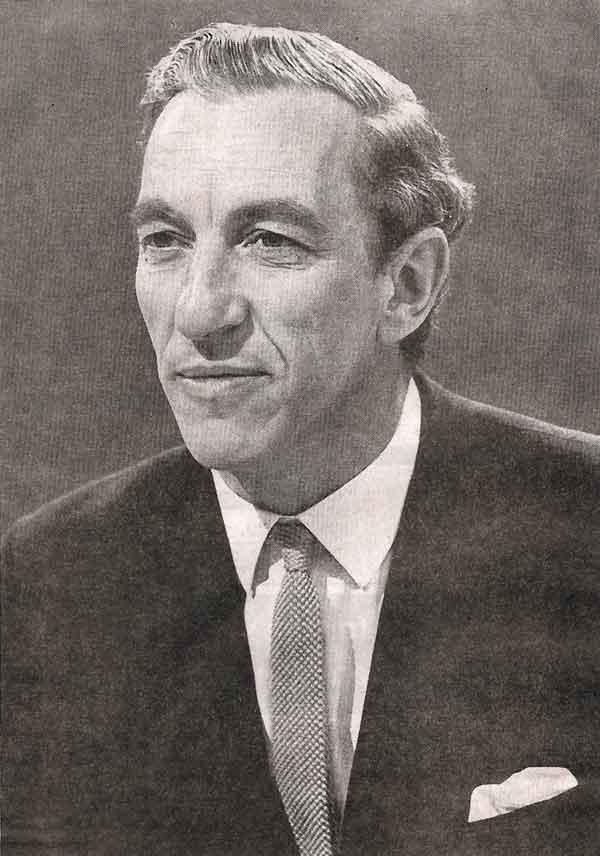

Sir Alan Smith joined 93 Sqn from 616 Sqn

where he had been Douglas Bader's wingman.

In November 1942 Alan Smith joined No 93 Squadron as it departed for north Africa to

take part in Operation Torch, the landings in Morocco and Algeria. Flying from airfields

in Algeria, Smith and his colleagues were used initially on ground support operations. As

the ground war and advance to Tunisia intensified, the Luftwaffe appeared in force and losses

mounted.

On November 22 1942 Smith shot down a Bf 109 over Tunisia and probably destroyed an

Italian Macchi 202 fighter. Four days later he accounted for two Focke Wulf 190s, and

by the end of the year he had shared in the destruction of two more FW 190s and damaged

a Stuka dive-bomber. At the end of January 1943 he returned to England, and two weeks

later was awarded a Bar to his DFC for his "inspired skill and great leadership".

On 31st December 1942 the squadron was established on the site of a new airfield at Soul-el-Khemis.

Sqn Ldr. Wilf Sizer assumed Command of No 93 Squadron on 13Feb43 until 19Aug43.

There followed until the end of the campaign in N. Africa on 13.5.43 a period of intense

operational activity, escorts were provided to bombers, and tac/recons and offensive sweeps

and patrols made over the areas - Tunis - Biserta, Pont du Faha and Mateur - Tabourba,

considerable damage being inflicted on M/T vehicles, roads, aerodromes and a number of enemy

aircraft destroyed and damaged. On 13th May 1943 the Squadron moved to Sebala and continued

operational work on convoy patrols and on 26th May 1943 moved to Mateur for a rest.

Malta

On 12th June 1943 the squadron moved to Hal Far, Malta and began a series of offensive sweeps

over Sicily in preparation for operation 'Husky' (the invasion of Sicily) on 10th July,

1943. On the day of the landings cover was provided by the squadrons' Spitfires and

numerous combats took place on that day and the following two days, the number of enemy

aircraft claimed to have been destroyed was 8 ½ and probably destroyed - 3.

Raymond Baxter, the famous post-war broadcaster joined the Squadron from July 1943 to July 1944.

Sicily

On 14th July 1943 the squadron advance party arrived at Comiso, Sicily and begun patrols over

Cantania, Syracuse and Cesaro. The rest of the squadron arrived at Comiso on the 20th

July 1943. Operations consisted of escorts to dive bombers attacking shipping in the Straits

of Messina and roads north of Etna.

Southern Italy

The squadron moved to Pachino on 31st July, 1943 and from there to Kasale on 2nd September 1943

patrols continuing all the time. On the 9th September 1943 the squadron was located at Falcone

from where on 26th September 1943 it embarked for Italy and was located at Battipaglio. Very

little flying was done from Battipaglio owing to unfavourable weather conditions and then

on 12th October 1943 the squadron moved to Capodochino, Naples, which had been occupied by the

allies on 1st October 1943. Battle line patrols and escorts to bombers as well as some convoy

patrols were the order of the day.

Route of 93 Sqn Airfield locations in Southern Italy.

On 16th January, 1944 a move was made to Lago airfield north of the Volturno River mouth

where the squadron was ready to provide cover for the landing at Anzio and Nettuno beaches,

on 22nd January 1944 and following days. For the next few months convoy patrols continued with

bomber escorts as well as fighter patrols over the Rome and Cassino areas. The squadron

claims to have shot down 5 enemy aircraft in March 1944 and 6 in April 1944 with the loss of two pilots.

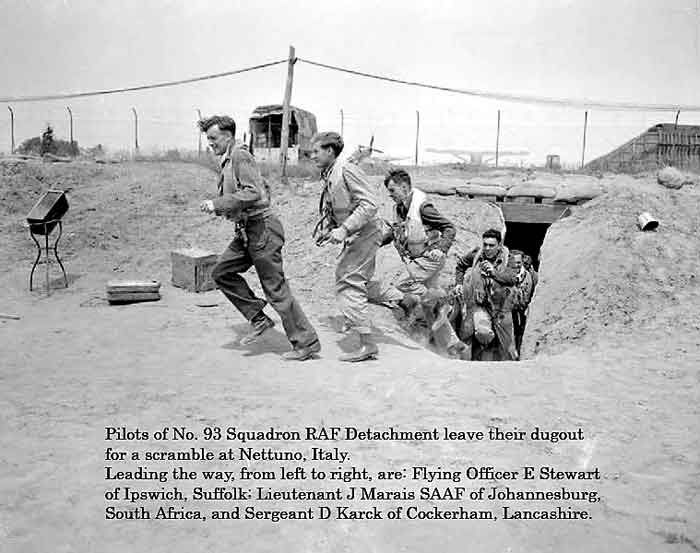

This was probably on the sand strip at Tre Cancelli, 3 miles north-east of Anzio

and therefore was taken between 5th and 13th June 1944.

On 5th June, 1944 the squadron was on then move again to Tre Cancelli a sand strip 3 miles

north east of Anzio where it remained 8 days and then moved to the concrete runway at Tarquinia

which had been heavily bombed by the Allies, the craters having been filled in with rubble.

Operating from this runway a good deal of undercarriage trouble was experienced, due mostly to

dust. On 25th June 1944 a further move was made to Grosseto. There were no engagements with the

enemy during the month and flying generally was on a reduced scale.

Corsica

At the beginning of July 1944 a number of battle line patrols were made and sweeps as far north as

Ravenna and Bologna were included. On 5th July 1944 the squadron was again on the move this time

to Piombino where it stayed until 21st July 1944 carrying out patrols over Leghorn, Pisa and Gargona

areas and providing escort to bombers; a good deal of opposition was encountered during the

sorties. On 20th July 1944 the squadron aircraft flew to Calvi in Corsica to be followed by the

ground personnel.

South of France

The first fortnight of August 1944 consisted of intensive patrols of southern France in preparation

for the landings which were made on 15th August 1944. Enemy radar stations were attacked two days

before the invasion. Five days after the landings had been affected the squadron aircraft left

Calvi and landed at the newly constructed strip at Ramatuelle, Southern France and carried out

patrols, escorts and staffing missions between Lyon and Macon. On one of these missions on 29th

August 1944 3 locomotives were destroyed and other trucks damaged, a staff car was wrecked, six

trucks set on fire and four others badly damaged. On 26th August 1944 the squadron moved to a new

landing strip in Sisterone.

Northern Italy

Armed recces and sweeps continued with successful attacks on trains and M.T. vehicles over the

Lyon - Chalon and Dijon - Belfort areas. A move was made to Bron airfield at Lyon on 10th

September 1944 and then on 28th September 1944 the squadron aircraft flew to La Jasse preparatory to moving

back to Italy, where it arrived on 14th October 1944 at Peretola. Weather conditions were very bad

during the remainder of the month and few operational sorties were flown.

Early in the following month the conversion of the squadron to a fighter/bomber squadron was

commenced and by 20 November 1944 the first bombing mission was carried out when Filo was bombed from

10-14,000 feet. Direct hits were obtained on houses and on roads west of Filo. The squadron was

then operating from Rimini having moved there on 16th November 1944.

December 1944 saw a full months flying, dive bombing results were excellent, the squadron scoring the

highest percentage of hits in the Wing. The squadron also began to do long range escorts to both

medium bombers and Kittyhawks attacking targets in Northern Italy and Jugoslavia. These sorties

continued in 1945 and in January 1945 the squadron again scored the highest percentage of direct hits

in the Wing. Targets attacked were marshalling yards, road and rail bridges, gun positions and

barges.

On 18th February 1945 a move was made to Ravenna from where targets were attacked at Udine, Meolo,

Cittadella, Gottingola, Bassano - Castel - Veneto, Treviso and long range escorts provided to

Gorizia, Longarone and Casarsa.

The final offensive in the Italian Campaign which began on 9th April 1945 saw the squadron working

at full strength. For the first 8 days of the month objectives were mainly rail cuts on the

Rouigo - Padova, Vicenza - Cittadella lines and many cuts were affected. Bombing and straffing

attacks were also directed against enemy occupied sites on Islands in Lake Commachio and near

to Port Garibaldi and it was during these operations that blaze bombs were used for the first time.

They proved most effective. The blaze bomb attacks were followed by H.E. bombs in the same areas.

The 8th Army push began on 9th April 1945 and in the afternoon of that day twelve aircraft of No. 93

Squadron in conjunction with aircraft of other squadrons attacked an area on the Senlo River to

prepare the way for advancing troops.

Until the end of the month there was much activity and numerous sorties were flown, mostly

against buildings and strong points. As enemy resistance began to lesson, Army Support targets

became few and armed recces and offensive patrols became the order of the day. On 30th April 1945,

the last day on which the squadron was called on the attack

the record number of 41 tanks, cars, and transport vehicles were destroyed and 21 damaged.

Pilot Officer John Andrew "Bud" Allen RCAF, seconded to 93 Squadron R.A.F.

who was killed on operations in Northern Italy on 12 April 1945.

[Click to see more details.]

Klagenfurt - Southern Austria

On 5th May 1945 the squadron moved to Rivolto airfield near Udine where some area recces were flown,

some extending to Austria. On 15th May 1945 the squadron moved to Klagenfurt, Austria. Several

Tac/R sorties were flown to check up on transport concentrations and movements but these ceased

after 18th May 1945.

The squadron took part in the Desert Air Force fly past at Udine on 28th May 1945.

Squadron Disbanded

The squadron was disbanded on 5th September, 1945.

No 237 Sqn Renumbered 93 - Equipped with Mustangs Northern Italy.

Final Disbandment at End of WWII

On 1st January, 1946 No. 237 Squadron was renumbered No. 93 Squadron.

It was located at Lavariano, Italy equipped with Mustang aircraft. The squadron moved

to Tissano during the summer and finally disbanded at Treviso on 30th December, 1946.

Reformed Nov 1950 Celle, Germany - Vampires Mk.5

The squadron reformed on 15th November, 1950 at Celle, B.A.F.O. equipped with Vampire Mk.5

aircraft. At various times the Squadron also held training aircraft looked after by Station

Flight. These included: Meteor Mk.7, Vampire T.11, Tiger Moth and Prentice.

Moved to Jever - March 1952 - Sabres, Hunter 4s and 6's

It moved to Jever in March, 1952 and upgraded to Vampire Mk.9's in November, 1953. In January,

1954 the Squadron won the 2ATAF Duncan Air-to-Air Gunnery Trophy. The Vampire Mk.9s were

exchanged for Sabre Mk.4's in April, 1954. In January, 1956 it received it's first Hunter

Mk.4's. These were changed for the aircraft it finally operated, Hunter F.Mk.6's in April, 1957.

Wins 2ATAF Duncan Gunnery Trophy Again

Before Disbanding Finally December 1960

In November, 1960 it was unexpectedly moved to Sylt while Jever's runways were being repaired.

With no practice or preparation, No. 93 Squadron carried off the 2nd Allied Tactical Air Force

Duncan trophy for Air-to-Air Gunnery with the highest score in the history of the trophy.

A fitting sign-off for the Squadron's final disbandment on 31st December, 1960.

COMMANDING OFFICERS NO 93 SQUADRON

Wing Commander J W Homer 7Dec40

Wing Commander M B Hamilton 23Apr41 to 6Dec41

Squadron Leader G H Nelson-Edwards, DFC 1Jun42

Squadron Leader W M Sizer, DFC 13Feb43

Squadron Leader K F MacDonald 20Aug43 killed 11Sep43

Squadron Leader D F Westenra, DFC, RNZAF 14Sep43

Squadron Leader J H Cleote 8Feb44

Squadron Leader L E Trenorden 19Sep44

Major A Sachs, DFC SAAF 28Sep44

Major T R J Taylor, DFC SAAF

16Feb45-5Sep45

Squadron Leader P F Steib 1Jan46

Squadron Leader R F H Pughe, DFC 14Aug46 to 30Dec46

Squadron Leader S M McGregor 15Nov50

Squadron Leader R N G Allen, DFC 21May53

Squadron Leader D F M Browne, AFC 18Sep54

Squadron Leader H Minnis, AFC 12Dec56

Squadron Leader D White 17Jun59

Squadron Leader M O Bergh 22Mar60 to 31Dec60

LOCATIONS

Middle Wallop England 7.12.40 - 6.12.41

Andreas Isle of Man 1.6.42

Wansford England 8.9.42

Algiers N. Africa 22.11.42

Souk-el-Khemis N. Africa 31.12.42

Sebala N. Africa 13.5.43

Mateur N. Africa 26.5.43

Hal Far Malta 12.6.43

Comiso Sicily 14.7.43

Pachino Sicily 31.7.43

Kasale Sicily 2.9.43

Falcone Sicily 9.9.43

Battipaglio Italy 28.9.43

Capodochino, Naples Italy 12.10.43

Lago Italy 16.1.44

Trecancelli Italy 5.6.44

Tarquinia Italy 13.6.44

Grosseto Italy 25.6.44

Piombino Italy 5.7.44

Calvi Corsica 20.7.44

Ramatuelle S. France 21.8.44

Sisterone S. France 26.8.44

Bron, Nr Lyon S. France 10.9.44

Peretola Italy 14.10.44

Rimini Italy 16.11.44

Ravenna Italy 18.2.45

Rivolto Italy 5.5.45

Klagenfurt Austria 15.5.45 Disbanded

Lavariano Italy 1.1.46 - 5.9.45

Tissano Italy 1.8.46

Treviso Italy 30.12.46 Disbanded

Celle Germany 15.11.50

Jever Germany 4.3.52 - 31.12.60 Disbanded

|