Dr Keith Thomas very kindly did some research for me on the web and came

up with the following information:

Jever airfield was four Kilometres south of Jever town [ 53.52 N 07.53E]

and 7 metres [ 24 feet above sea level]. The airfield was started in 1935 and

became operational in 1936 with Coastal Fighter Group 136 flying He 51's and

later Ju 87b, but its contact with the RAF came after the Polish incursion and

they brought back Messerschmitt Bf 110's and 109's.

FIRST AIR RAID ON THE BRITISH ISLES

At the beginning of the War the Luftwaffe had only 12 JU 88s

in the front-line and they were based at Jever operating as Kampfgeschwader

Wunderbomber 1/KG 25 commanded by Hauptman Helmut Pohle who, at 32, was a

veteran who had served as a general staff officer at the Air Ministry in Berlin,

and had seen combat in the Spanish Civil War. On 7 September 1939,

the 2 Staffeln of 1/KG25 were re-designated becoming 1/KG30 and began an

intensive period of training with their new JG88s.

On 26 September 1939 the Luftwaffe mounted an unsuccessful attack on

Royal Naval carrier HMS Ark Royal and, as a consequence, Pohle was

summoned to a meeting with Goering in which he was told that there

were only a few British ships making things difficult for Germany

and that once these had been dealt with, the way would be clear for

Scharnhorst and Gneisenau to dominate the seas. Pohle assured Goering

that his crews were ready to take on the mission and agreed that 1/KG

30 would move to Sylt from whence the first attack on mainland Britain

and the Royal Navy ships would be mounted. Pohle led his 12 aircraft

in scattered formations of 3, each aircraft carrying only 2 x 500kg

bombs because of the long range of the mission. The Luftwaffe intelligence

staff insisted that there were no Spitfires in Scotland and Pohle and his

crews were unpleasantly surprised to be intercepted by the Spitfires of

602 and 603 Squadrons: the raiders lost 3 aircraft and 8 aircrew killed,

Pohle's aircraft was one of the 3 and he became a prisoner of war and

survived into late old age.

Source: The Definitive History of No 603 Sqn RAUXAF

It was from Jever that Wolfgang Flack flew his BF110'c Zerstörer taking

out the Wellingtons heading for Bremen, he didn't get it all his own way and

came down on Wangerooge. Why mention him? The quote is that he was the most

influential Luftwaffe officer of the World War 2 ...there is a book about him

and he went on to be a night fighter. He wasn't long at Jever.

In the book "The First and the Last" by Adolf Galland 'The rise and fall

of the Luftwaffe - by Germany's greatest fighter pilot', there is a report that

Galland was charged with providing fighter cover for the dash of the three capital

ships, Gneisnau, Scharnhorst, and Prinz Eugen from Brest to Norway starting on 11th

February 1942. He didn't have enough aircraft, as many had been sent east, so he

had them hopping along the Channel coast in shifts to provide a constant 'umbrella'

over the flotilla. His last airfield, covering the German Bight, was Jever!

Here is an interesting extract from the story of Alfred Fane, a reconnaissance

Spitfire pilot involved in tracking the Tirpitz:

"After a distance of 1,180 miles and a flight time of five hours 20 minutes,

Alfred landed at Wick to be rushed off to Operations where he reported what

he had seen after which, and in his words, there was "a flap" from Group, Coastal

Command and the Admiralty.

The Tirpitz now became the priority. Alfred flew another successful sortie

on 2 February and Flt Lt Tony Hill did the same on 15 February but by now the

Luftwaffe had to do something to stop these missions from being carried out with

impunity, especially when the battleship Prinz Eugen, damaged by a mine on

12 February 1942 during the breakout of German warships from Brest, arrived at

Trondheim. Hauptmann Fritz Losigkeit, an experienced fighter pilot who had just

returned from Japan, was told to form Jagdgruppe Losigkeit, the three Staffel being

formed from 8/Jagdgeschwader 1, 2/Jagdgeschwader 1 and the operational elements of

Jagdgfliegerschule 1 and 2. Getting to Trondheim was made hard by the weather-they

left Jever in northern Germany 15 February via Esbjerg and Aalborg in Denmark and

then Gardermoen in Norway, not arriving at Trondheim until 24 February which

coincided with the arrival of the Prinz Eugen and Admiral Scheer. The presence of

more German warships soon attracted the RAF's attentions as one German pilot,

Leutnant Heinz Knoke recorded in his diary on 26 February 1942:

'At 1312 hrs our sound detectors along the coast report the approach of

a single enemy aircraft coming in at high speed. A reconnaissance?'

'At 1315 hrs, I take off from the airfield alone. I am determined to get

the bastard. I climb to an altitude of 25,000 feet. Our patrol already in the

air is ordered to continue circling above the cruiser Prinz Eugen.'

"Repeatedly I scan the skies for the intruder. There is not a Tommy to be

seen. Reports from the ground are lacking in precision. They are no value to me

as they are too vague. After 85 minutes I give up and land again."

Knoke had tried to intercept a sortie flown by Fg Off Edward Lee whose objective

was Bergen and Haugesund but Lee only managed to cover Stavanger, some distance

from Trondhei

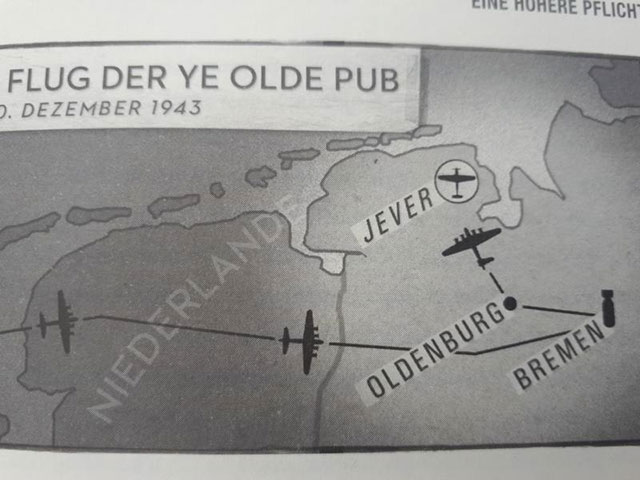

Charlie Brown and Franz Stigler incident

The Charlie Brown and Franz Stigler incident occurred on 20 December 1943,

when, after a successful bomb run on Bremen, 2nd Lt Charles "Charlie" Brown's B-17

Flying Fortress (named "Ye Olde Pub") was severely damaged by German fighters.

Luftwaffe pilot Franz Stigler had the opportunity to shoot down the crippled

bomber but did not do so, and instead escorted it over and past German-occupied

territory so as to protect it. After an extensive search by Brown, the two

pilots met each other 50 years later and developed a friendship that lasted

until Stigler's death in March 2008. Brown died only a few months later, in

November of the same year.

Pilots

2nd Lt Charles L. "Charlie" Brown ("a farm boy from Weston, West Virginia",

in his own words) was a B-17F pilot with the 379th Bombardment Group of the

United States Army Air Forces' (USAAF) 8th Air Force, stationed at RAF

Kimbolton in England. Franz Stigler, a former Lufthansa airline pilot from

Bavaria, was a veteran Luftwaffe fighter pilot attached to Jagdgeschwader 27

based at Jever.

Bremen mission

The mission was the Ye Olde Pub crew's first and targeted the Focke-Wulf

190 aircraft production facility in Bremen. The men of the 527th Bombardment

Squadron were informed in a pre-mission briefing that they might encounter

hundreds of German fighters. Bremen was guarded by more than 250 flak guns.

Brown's crew was assigned to fly "Purple Heart Corner," a spot on the edge

of the formation that was considered especially dangerous because the Germans

targeted the edges, instead of shooting straight through the middle of the

formation. However, since three bombers had to turn back because of mechanical

problems, Brown was told to move up to the front of the formation.

For this mission, Ye Olde Pub's crew consisted of:

2nd Lt Charles L. "Charlie" Brown (October 24, 1922 - November 24, 2008):

pilot/aircraft commander

2nd Lt. Spencer G. "Pinky" Luke (November 22, 1920 - April 2, 1985): co-pilot

2nd Lt. Albert A. "Doc" Sadok (August 23, 1921 - March 10, 2010): navigator

2nd Lt. Robert M. "Andy" Andrews (January 14, 1921 - February 23, 1996):

radio operator & bombardier

Sgt. Bertrand O. "Frenchy" Coulombe (March 1, 1924 - March 25, 2006):

top turret gunner and flight engineer

Sgt. Richard A. "Dick" Pechout (September 14, 1924 - January 5, 2013):

radio operator

Sgt. Hugh S. "Ecky" Eckenrode (August 9, 1920 - December 20, 1943): tail

gunner

Sgt. Lloyd H. Jennings (February 22, 1922 - October 3, 2016): left waist

gunner

Sgt. Alex "Russian" Yelesanko (January 31, 1914 - May 25, 1980): right

waist gunner

Sgt. Samuel W. "Blackie" Blackford (October 26, 1923 - June 16, 2001):

ball turret gunner

Bomb run

Brown's B-17 began its ten-minute bomb run at 8,320 m (27,300 ft)

with an outside air temperature of -60 °C (-76 °F). Before the bomber

released its bomb load, accurate flak shattered the Plexiglas nose,

knocked out the #2 engine and further damaged the #4 engine, which

was already in questionable condition and had to be throttled back

to prevent overspeeding. The damage slowed the bomber, Brown was

unable to remain with his formation and fell back as a straggler, a

position from which he came under sustained enemy attacks.

Fighter attacks

Brown's struggling B-17 was now attacked by over a dozen

enemy fighters (a combination of Messerschmitt Bf 109s and

Focke-Wulf Fw 190s) of JG 11 for more than ten minutes. Further

damage was sustained, including to the #3 engine, reducing it to

only half power (meaning the aircraft had effectively,

at best, 40% of its total rated power available). The bomber's

internal oxygen, hydraulic and electrical systems were also damaged,

and had lost half of its rudder and port (left side) elevator, as

well as its nose cone. Several of the gunners' weapons had jammed,

most likely as a result of the loss of on-board systems, leading

to frozen firing mechanisms. This left the bomber with only two

dorsal turret guns plus one of the three forward-firing nose guns

(from 11 available) for defense. Many of the crew were wounded:

the tail gunner, Eckenrode, had been decapitated by a direct hit

from a cannon shell, while Yelesanko was critically wounded in

the leg by shrapnel, Blackford's feet were frozen due to shorted-out

heating wires in his uniform, Pechout had been hit in the eye by a

cannon shell and Brown was wounded in his right shoulder. The

morphine syrettes carried onboard had also frozen, complicating

first-aid efforts by the crew, while the radio was destroyed and

the bomber's exterior heavily damaged. Miraculously, all but

Eckenrode survived. The crew discussed the possibility of

bailing out of the aircraft, but realized Yelesanko would be

unable to make a safe landing with his injury. Unwilling to

leave him behind in the plane, they flew on.

Franz Stigler

Brown's damaged, straggling bomber was spotted by Germans

on the ground, including Franz Stigler (then an ace with 27

victories), who was refueling and rearming at Jever airfield.

He soon took off in his Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 (which had a

.50-cal. Browning machine gun bullet embedded in its radiator,

risking the engine overheating) and quickly caught up with

Brown's plane. Through openings torn in the damaged bomber's

airframe by flak and machine gun fire, Stigler was able to see

the injured and incapacitated crew. To the American pilot's

surprise, the German did not open fire on the crippled bomber.

Stigler instead recalled the words of one of his commanding

officers from Jagdgeschwader 27, Gustav Rödel, during his

time fighting in North Africa: "If I ever see or hear of

you shooting at a man in a parachute, I will shoot you myself.

Stigler later commented, "To me, it was just like they were

in a parachute. I saw them and I couldn't shoot them down."

Twice Stigler tried to persuade Brown to land his plane

at a German airfield and surrender, or divert to nearby

neutral Sweden, where he and his crew would receive medical

treatment and be interned for the remainder of the war.

However Brown and the crew of the B-17 did not understand

what Stigler was trying to mouth and gesture to them,

and so flew on. Stigler later told Brown he was trying

to get them to fly to Sweden. He then flew near Brown's

plane in close formation on the bomber's' port side wing,

so that German anti-aircraft units would not target it,

they reached open water. Brown, still unsure of Stigler's

intentions, ordered his dorsal turret gunner to target

his guns on Stigler but not open fire, to warn him off.

Understanding the message and certain that the bomber was

finally out of German airspace, Stigler departed with a

salute.

Landing

Brown managed to fly the 250 mi (400 km) across the

North Sea and land his plane at RAF Seething, home of the

448th Bomb Group and at the post flight debriefing informed

his officers about how a German fighter pilot had let him

go. He was told not to repeat this to the rest of the

unit so as not to build any positive sentiment about

enemy pilots, lest other damaged bombers hold their

fire on incoming fighter planes hoping to be rescued,

only to be shot down. Brown commented, "Someone decided

you can't be human and be flying in a German cockpit."

Stigler said nothing of the incident to his commanding

officers, knowing that a German pilot who spared the

enemy while in combat risked a court-martial. Brown went

on to complete a combat tour. Franz Stigler later

served as a Messerschmitt Me 262 jet-fighter pilot in

Jagdverband 44 until the end of the war.

Postwar and meeting of pilots

After the war, Brown returned home to West Virginia

and went to college, returning to the newly established

U.S. Air Force in 1949 and serving until 1965. Later, as

a U.S. State Department Foreign Service Officer, he made

numerous trips to Laos and Vietnam. In 1972 he retired

from government service and moved to Miami, Florida to

become an inventor.

Stigler moved to Canada in 1953 and became a

successful businessman.

In 1986, the retired Lt. Col. Brown was asked

to speak at a combat pilot reunion event called a

"Gathering of the Eagles" at the Air Command and

Staff College at Maxwell AFB, Alabama. Someone

asked him if he had any memorable missions during

World War II; he thought for a minute and recalled

the story of Stigler's escort and salute. Afterwards,

Brown decided he should try to find the unknown German

pilot.

After four years of searching vainly for U.S.

Army Air Forces, U.S. Air Force and West German

air force records that might shed some light on

who the other pilot was, Brown had come up with little.

He then wrote a letter to a combat pilot association

newsletter. A few months later he received a letter

from Stigler, who was now living in Canada. "I was

the one," it said. When they spoke on the phone,

Stigler described his plane, the escort and salute,

confirming everything that Brown needed to hear to know

he was the German fighter pilot involved in the incident.

Between 1990 and 2008, Charlie Brown and Franz

Stigler became close friends and remained so until

their deaths within several months of each other in 2008.

The incident was later recorded by Adam Makos in

the biographical novel A Higher Call (released in 2012).

The Swedish Power Metal band Sabaton wrote a song for

their seventh studio album Heroes, the second track

"No Bullets Fly". (Thanks to Marcus Christ.)

Jever airfield was literally carved out of the

surrounding forest. The local rumours claimed that,

as it was only a grass airfield during the war, it was

very difficult to recognise from the air and that it

was never bombed or even discovered by the RAF.

Keith says he had the same information as me that

suggested that the airfield was handed over intact

at the end of the conflict, it was not apparently

recognised for what it was but Keith's next door

neighbour in Beethoven Strasse was Vic Azzaro and he

recollected being attacked while flying over Jever.

Translation from the German introduction to the

RAF Jever Open Day 6th June 1959 by Air Chief Marshal

Sir Humphrey Edwardes Jones KCB; CBE; DFC; AFC; RAF

Commander-in-Chief, 2nd Tactical Air Force (Germany):

"An airfield for light recreational aircraft

from the middle of the 1920s to 1935, an operating

base for the Luftwaffe from 1935 to 1945 and today,

a fighter base for the Royal Air Force within the

NATO defence system - these are the three development

periods of Jever airfield.

After the first World War the Focke-Wulf Works

in Bremen had a small sports airfield built on the

edge of the Upjever forest. This was occupied by

seven light sporting planes. The Luftwaffe took

the airfield over in 1935 and within a year extended

it by felling a large part of the Jever forest to

form a fighter base. Hangars, quarters, a hospital,

and underground aviation fuel dump sprang up in quick

succession, so that on 1st May 1936 General Mulch was

able to hand over the airfield in working order to

the 1st Commanding Officer, Hauptmann Melrich.

In June 1937 Jever airfield was manned by a

fighter wing with three squadrons.

In September 1939, Me 109s and Me 110s were

stationed at Jever. They flew their first sorties

against 22 Wellington bombers, which planned an attack

on German ships off Schillig and Wilhelmshaven.

In 1943 additional Ju 52s came to Jever.

These were used as mine detectors. Towards

the end of the war the Me 109 and Me 110 fighters

were withdrawn from Jever and replaced by Ju 188

night fighters.

The Luftwaffe had not extended the airfield

any further and when the English took it over

they used it as an auxiliary base at first.

Between 1945 and 1951 the airfield was

garrisoned by Poles, Canadians, Danes and

Jewish immigrants."

From Volker Ullrich's book "Eight Days in May

- How Germany's War Ended" (Thanks to Mick Davis):

British forces quickly advanced to the Elbe,

their Polish comrades headed north to take Jever and Wilhelmshaven.

"In the villages and town districts we pass through (there are) white

flags and celebrating crowds of liberated POWs and slave labourers

lining the streets," Skibinski reported. "At the hotel where our

brigade was to set up its headquarters, a gigantic Polish flag

was already flying." Before entering the hotel, the Polish

colonel was received by the regional councillor, the mayor,

and the hotel owner. "If anyone in the city feels like hurling

a stick at a Polish soldiers or throwing a stone at anywhere Poles are quartered,

you three will be hanged and the city will go up in smoke, Skibinski was said

to have threatened."

Three days earlier, in the late afternoon of May 3, 1945, something

unusual had occurred in Jever. More than two thousand people had gathered

in the city's largest square, Der Alte Markt, to protest about the plan

to defend the city against approaching Allied troops. The senior city

administrator, Hermannh Ott, tried to pacify the crowd and was hauled

down from the podium. The head of the Nazi Party in Friesland district,

Hans Flugel, did not have better luck. His exhortations to hold out

were drowned out by cries of "String him up from a streetlight,

this golden pheasant." Two men grabbed Flugel and stripped him of

his pistols, as courageous citizens raised a white flag from the

tower of Jever Castle. They were arrested by a company of naval

soldiers on the evening of May 4 and taken to Wilhelmshaven.

They likely only escaped with their lives because the partial

capitulation of German troops in the northwest of the country was

announced shortly thereafter.

Many of Jever's residents were aware of what their fellow

Germans had done in Poland and feared the worst when the Polish

forces arrived. But their terror proved unfounded. "Originally,

we were afraid of the Poles, but they behaved beyond reproach,"

remembered one eyewitness. Polish troops withdrew from Jever

and Wilhelmshaven on May 20 and 21 and were replaced by British and

Canadian units.

|