| Second Lieutenant Montague Vincent Pocock MM RFC - Wireless Operator 4 Sqn WWI | ||

|

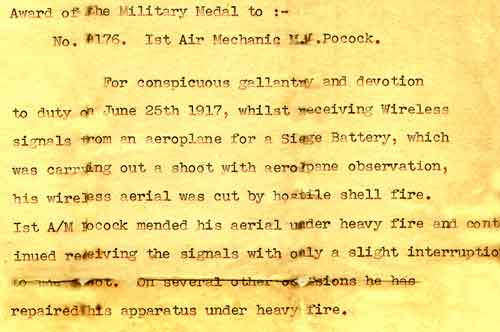

Citation for the award of the Military Medal to 1st Air Mechanic Monty Pocock for gallantry on 25th June 1917. It reads: (Click to see full report in 4 squadron History.)

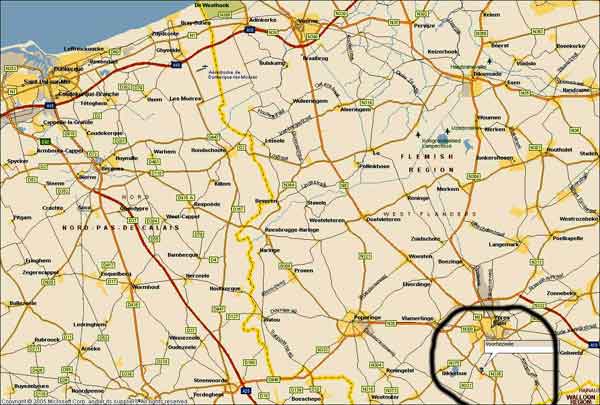

Map showing Siege Battery at Voorhezeele in relation to Ypres and Dunkirk. The following is an extract from the 4 Squadron History describing the role of the Ground Wireless Operators:

Much has been said regarding the difficulties of the aircrew when engaged in artillery spotting, but

the wireless operators on the ground had problems of a similar magnitude. Although on the strength of a

squadron, they were detached to siege batteries of the Royal Artillery and so were exposed to greater

dangers than other members of the groundcrew. Their living quarters were invariably bad, and with each

man being responsible for the maintenance and operation of his equipment, his workload was high.

The equipment comprised a "Wireless Set Receiving Mark 3", which was essentially a powerful crystal

set, and a thirty foot mast which broke down into eight sections. This was used to support the aerial,

which had to be at right angles to the Front and sloped down to an eight foot pole near to the wireless

operators position. The operator was in telephone contact with various batteries and as such could be

responsible for a large portion of the Front. But his difficulties did not end there. German aircraft were

also engaged on artillery spotting duties, and obviously the sighting of his mast would indicate to them

the presence of a high value target. A wireless ground station would be very likely to come under sustained

artillery attack, and the operator had two alternatives; direct his aircraft to find the battery which was

shelling him, and engage it with counter-battery fire, or to pack up, lock stock and barrel, and move his

post to a new site. This would entail the laying of new telephone cables to the batteries under his control

and so the post would be effectively neutralised for a period even if the equipment was not destroyed.

The wireless operators of the RFC could indeed identify with the troops in the trenches.

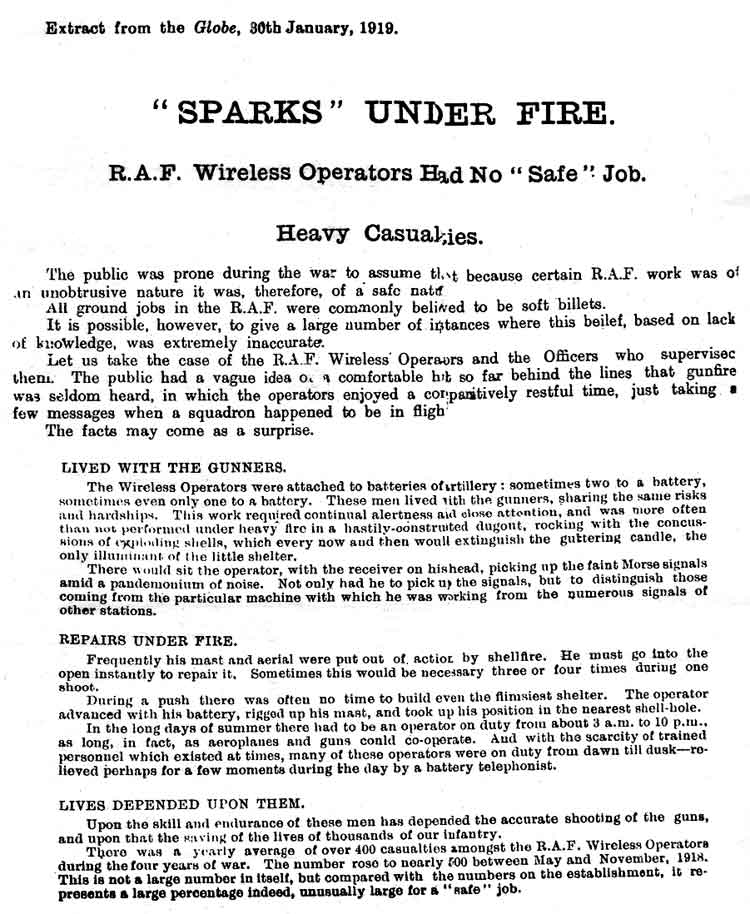

Extract from the Globe, 30th January, 1919 praising the role of the RAF Wireless Operators.

Example of the Message Form used by the RAF Wireless Operators in WWI.

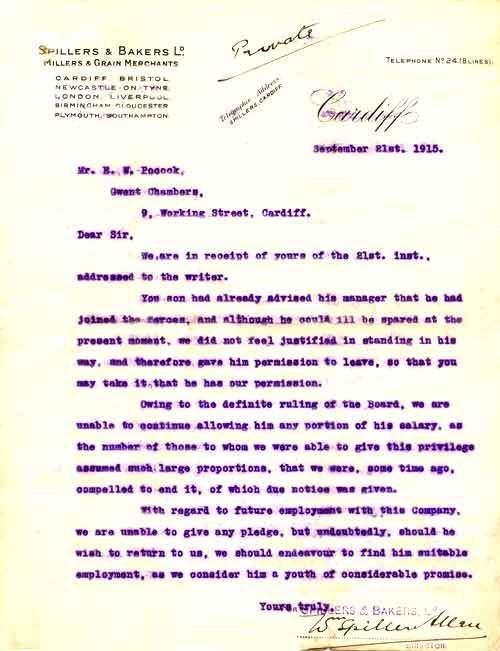

Mr E. W. Pocock, Gwent Chambers, 9, Working Street, Cardiff. Dear Sir, addressed to the writer. joined the forces, and although he could ill be spared at the present moment, we did not feel justified in standing in his way, and therefore gave permission to leave, so that you may take it that he has our permission. unable to continue allowing him any portion of his salary, as the number of those to whom we were able to give this privilege assumed such large proportions, that we were, some time ago, compelled to end it, of which notice was given. we are unable to give any pledge, but undoubtedly, should he wish to return to us, we should endeavour to find him suitable employment, as we consider him a youth of considerable promise.

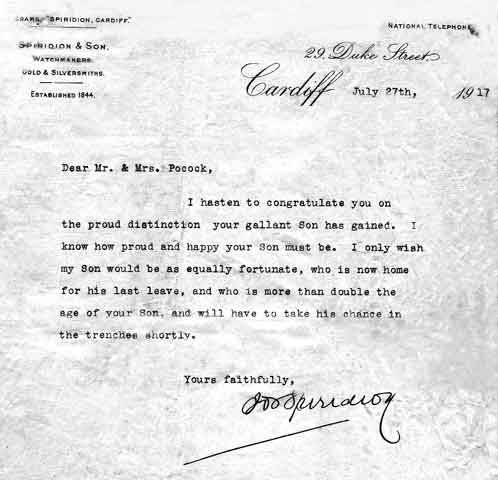

Letter of congratulations on Monty's award from Mr Spiridion of Cardiff dated 27th July 1917.

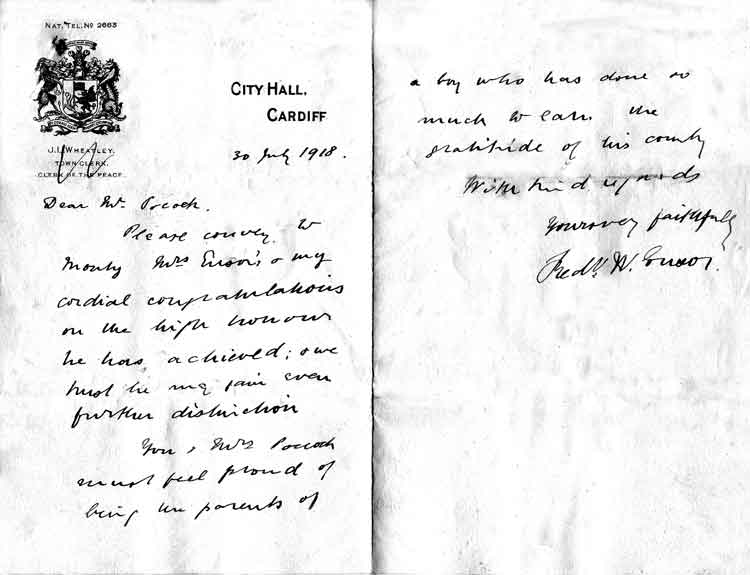

Letter of Congratulations from Cardiff City Hall dated 30Jul1918 which reads:

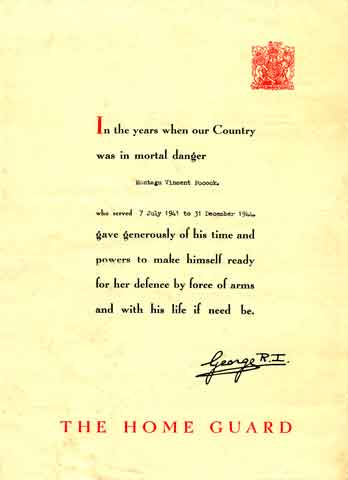

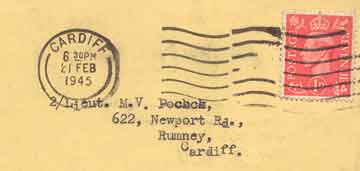

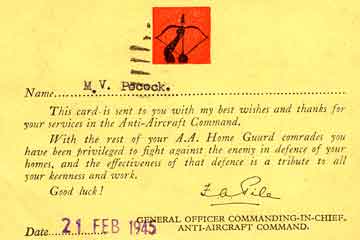

Monty also served in WWII in the Home Guard where he rose from Corporal to 2nd Lieutenant. Above is his certificate of Gratitude signed by the King.

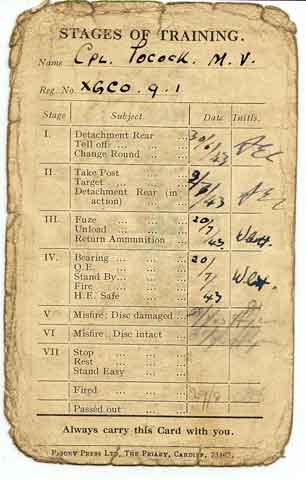

Well worn Stages of Training Card for Cpl Monty Pocock in WWII.

Proof of commissioning to 2nd Lieutenant Monty Pocock and his Certificate of Gratitude for his service in the Anti-Aircraft Role in the Home Guard in WWII. Wireless Operators Old Comrades AssociationWhen the Royal Flying Corps, Wireless Operators Old Comrades Association was founded just after the end of the 1914-1918 War by those who survived, it was realized that such an Association was unique, inasmuch as there could never be such a Unit again. The unit was formed late 1914 and in April 1918 it became incorporated in the R.A.F. Its existence was therefore of short duration, but the good work done in that short time vastly exceeded the period of time. The men who joined this Unit were only together for their initial training as they were afterwards transferred to Heavy and Light Artillery Batteries, some to the Cavalry others even on Monitors with the Fleet, and therefore had no chance of meeting up with one another except by the merest fluke. Infantry had their battalions and the Artillery had their batteries who thereby trained and fought with these units. The poor Wireless Operator however was on his own amongst a lot of strangers doing a job of work which no one understood except possibly the Senior Officers. He was a much maligned person as part of his equipment was a thirty foot steel mast which had to be erected on the battery site or wherever else he had to go, and that fact alone in the days of utmost care regarding camouflage was enough to infuriate anyone as it gave the position away. Still the Top Brass said it was essential otherwise we could not function.Some years ago, at one of our Dinners held in London, the surviving Operators were asked to send in their experiences showing names of places and names of Operators they met. The object being that when all the data had been collected, a booklet would be issued thereby giving details of places and names of Operators enabling Operators to say "Blimey, I was billeted in a broken down pig-sty only about 100 yards from that battery positioned in the cemetery". There was not to be any attempt in our "experiences" which bordered on the "Bravado" as this was fully understood. All which was needed were actual facts i.e. Battery Nos. Cavalry Squadrons, names of Operators met and positions where Operators were killed or wounded. The following pages are a transcript of the notes made by Monty Pocock giving his Details of Service during the 1914 - 1918 War. DETAILS OF SERVICE. - Monty Pocock, No. 9176. M.M. R.F. Corps.Present address: 622 Newport Road, Rumney, CARDIFF.1915May/June Saw an advertisement in the "TIMES" for Wireless Operators trained or untrained for service with the R.F.C. My capabilities as an operator were nil except for a very slight experience of an ordinary home made set. However I applied stating my meager qualifications.August. Received notification that if still interested, I was to reply, which I did, and in a couple of days I received forms which had to be filled up by M.Officer, together with Railway Warrant from Cardiff to London, single. If I was passed O.K. by M.O, I was to report at Horse Guards Parade ground at 8.30 a.m. on the date mentioned. The previous night I spent at the Union Jack Club in London. We left Horse Guards Parade in the morning complete with band and awkward suitcases and straw hats and marched to railway station for Farnborough where we spent about 6 solid weeks square bashing and Squad drill. Sept. A large number of would-be operators were then sent to the Poly, London, myself included to receive Wireless and Morse instruction. We were billeted at Riding House School. It was the practice to drill and erect wireless masts in the mornings and receive Morse and wireless instructions in the afternoons. This was altered after a while to vice versa, as it appears the nursemaids did not go out until the afternoons and this arrangement suited the drill corporals to the utmost as these drills and exercises took place at Regents Park. Things progressed very favorably for a while but with the arrival of snow and slush and our transfer to High Street, Kensington, where we were billeted, things altered, as it meant having to leave High St. at 6 a.m. and march to Regent St. (having about 1/2 hour squad drill at Regent Park en route). We then proceeded to breakfast, which if in funds, consisted of bangers tea and bread and butter? In those days we received about 1/9d (£6.91=Aug10) per day subsistence allowance, and by the end of the week, we were starving. 1916Jan The weather eventually got worse and around January 1916 the streets where we marched were covered by masses of slush. It was when we arrived back at Regent St. on some such morning, fully expecting to be dismissed, when Sgt. Major Ramsden (heaven rest his soul) took it into his head that a further march would do us good, so up Oxford St & Tottenhan Court Rd. we went, not singing as was usual and by devious routes, got back to the Poly, where we marched into the Gym. soaking wet and really fed up. We were forced to do some physical jerks etc. and quite a number of the chaps passed out. Of course by this time it was about 10 a.m. and as we had left Kensington at 6 a.m. and had had no grub, we were all feeling a bit groggy. Then the fun started, we point blank refused to do any more drill until we had been fortified. We were then locked in the Gym and after a while were marched into the adjoining cinema where the Major read out the Riot Act, or some such document. He explained we were being held for Mutiny on active service one can imagine what we were thinking about of the dubious popular Sgt. Major Ramsden. Eventually the 3 oldest soldiers were marched away under guard to Farnborough for trial. I was the fourth oldest soldier, my Godfathers, I shudder to think what would have happened if I had been the third oldest. After this episode, we were given decent N.C.O's and things proceeded very satisfactorily. We had quite a long spell marching behind a Guards Band and pipers' band, escorting recruits to Chelsea Barracks, where they were signed on. These were very happy times, but eventually there was a passing out of a big percentage of operators, which we now were, and the O/C was so pleased he said he would give us a long week-end leave from Thursday to Monday something went wrong because on the Thursday they issued about 20 of us with overseas kit for France, and that night were put on the train for Southampton.May 12th Boarded a steamer at Southampton and sailed as far as the tip of the I.O.Wight, where we anchored overnight because of submarines. May 13th Arrived at Le Havre but did not land, proceeded up river to Rouen where we landed. After a short arm inspection, we were allowed to go into town for a couple of hours. As it was our first visit to France for most, the Corporal in charge offered to assist. His instructions were to "fall out on the right all who want to go to the Cathedral", and on the "left all who want to go to the Red Lamps". Well most of us had seen lots of Cathedrals in the past, so we fell out on the left as we had no idea what Red Lamps were and were naturally curious. After our curiosity was so vulgarly satisfied, we then reverted back to the Cathedral which was most interesting (not that the other places weren't either). 14-5-16 We were then entrained for an unknown destination. The carriages were good (for officers only) ours were the 9 chevaux ou 40 hommes variety. We spent 24 hours in this truck, we went through Etaples and at midnight spent a couple of hours in Amiens Station (under guard). The train traveled very slowly, and it was the custom, if you were thirsty, to walk along the outsides of the trucks towards the front of the train, and when a village was in the offing, to jump off, have your drink, and catch the tail end of the train, which was exceptionally long. 15-5-16 Some us were dropped off near HESDIN and a tender took us to No. 21 Squad. At LAMBUS, which had R.E.7s, a bigger version of R.E.8., the Wireless Officer was Lieut. Knight, a short young chap. Our main duties here were to camera Obscura (?) practice and take press news. 16-5-16 It was my duty to take the mid-night news. It was thundering and lightening flashes were very frequent and it was also raining heavens hard. Well the signals from Poldhu, which were usually weak, were this night particularly faint, and coupled with the heavy rain falling on the corrugated roof of iron, things were well nigh hopeless. I should imagine I received about a quarter of the news, but when I read what I had taken down, I really had the breeze well up. I did not know whether Lord Kitchener had been drowned, promoted or sacked. All I could pick up clearly was what he had done in the past, and H.M.S. Hampshire which had been sunk. Being exceptionally raw at the time, I awoke the Major of the Squadron (he was a one armed man) at 2 a.m. and explained what I had received. I still blush at the things he called me. However he was decent enough to apologise to me the next morning when the news of Lord Kitcheners death came through. It was from this 21 Squad. that we received wireless instructions regarding the movement of cavalry, and two of us took a Receiver, masts and a special set of ground signals to MONTREUIL near the coast. The set was installed in a small cottage, and a small room in which we were taking the signals was filled with brass hats of all types, Brigadiers, Colonels and what have you, all jabbering away at once. I have never heard of an instance, before or since, when such a collection of Brass was told not to make such noise by an ordinary 2nd Class Air Mechanic. I had such a dirty look from all and sundry, but at least it had a wonderful effect - there was not a murmur afterwards. I was congratulated afterwards by the Officer in charge for being so forthright. June I was told I would in future be working with the cavalry. During June a few of us went to CANDAS and nearby FIENVILLES, why, don't ask me, but we certainly unloaded quite a large number of trucks of coal. What this had to do with Cavalry heaven knows, if it had been dung, it would have rung a bell. After about a fortnight of this work and persistent grousing, we were shifted to No. 34. Sqdn. And when we awoke next morning we found we were in BERTANGLES together with about 30 other operators, all doing fatigues. We would parade at 8.0 a.m. have roll call, and after dismissal of the Flights, the Wireless Section were told to standfast. We would then collect wheel barrows, picks and shovels and proceed to a heap of chalk. Whichever job we did we did not over exert ourselves as we were so fed up. In the one case we would take it in turns to go into the holes we were ringing and play cards or sleep, in the other we would hurry up and load the lorry, and if we had any money, we would spend our time in the estaminets. These jobs came to sudden stop. The Wireless Major called at the Squadron to see if there were a couple of Operators who could be spared. When he heard there were about 30 doing fatigues, he nearly did his nut. He said he had been scouring France for Operators in view of the coming offensive. We went to ST. OMER that evening where we were sorted out to observation Squadrons. June/July Now it is a case of going from the sublime to the gor blimey. From ringing holes with chalk, I was posted to 121 Brigade R.F.A whose job it was to clear the barbed wire in front of the German trenches in front of FRICOURT (Somme). This was done with the use of aerial observation. I thought what a cushy job, living in my own tent and beautiful weather. I think I only had a tent for 1½ days because then the SOMME offensive started. What a bombardment - everything went up. The battery was still firing but all surplus gear was packed up ready for the time the troops went over the top. After a while we moved up, not far, but sufficiently so to enable us to shell the German trenches and machine gun posts. After a couple of weeks and wishing I was back ringing holes with chalk, the Brigade was relieved. I was then sent to a Canadian Battery to relieve an Operator who had been wounded. I never knew his name. I was eventually relieved by a Corporal and was taken back to BECORDEL for a few days. Here I met Corp. Tullet and spent a few comfortable days living in a tent again. I then went back to the batteries either relieving or temporarily replacing. August 1916 I was then sent to 121 Heavy Battery, 60 pounders, with whom I spent a long time, leaving them at TRONES WOOD to go to 126 Seige Battery. R.G.A. 8" How. at LONGUEVAL. Sept. Here I met Corp. Bolton with whom I served as second man. Unfortunately after about a fortnight with the battery, Bolton was severely wounded, and from what I could see, he would certainly lose his right leg from the thigh. I was then left on my own in the battery with the promise of relief in the near future. Promises - hell. It was when I was with this battery I got in touch with another Operator named Idris Williams, a Welshman from GELLI, South Wales. He had already been awarded the M.M. He was serving with 120 Seige battery. Their guns, 8" How. were in place in the sunken road behind us at LONGUEVAL. I also got in touch with Operator Rogers, he was with a battery on our left. We used to check up with one another on our N.F's Zone calls. Unfortunately he was killed one night. Oct./Nov. Our battery did a lot of good counter-battery work from this position. We were operating with No. 3. Squadron which flew Morane-Parasol monoplanes. Call sign D, our battery was X, and for a long time worked with an Observer numbered 34 (forgotten his name, but he was an ex-operator). Dec. Just before Xmas I was promoted to 1st Class A.M. and assumed correctly I would not have a second man. Christmas Eve, the Battery shifted position to GINCHY (Somme) near WATERLOT FARM, I went with them. Behind us was 121 S. Battery, 9.2" Hows. The operator was a chap named Childs, an Australian. This was another successful position for the battery, although we lost a lot of gunners. My dug-out was close to a brickworks, which was leveled to the ground. In front was a pond and one morning after the nights usual strafe, two German soldiers bodies had been blown out of the pond. Their uniforms and bodies were perfectly clean, I thought there had been a night raid. Our Battery Major was a man named Woods, who came from MONTROSE, Scotland, and being a Scot, he promised us a good meal for New Years Day. He wangled a pig and it was the cooks job to fatten it up. It was tethered to the cook house. Just before New Years Eve, Jerry got an O.K. on the pig and cookhouse, there wasn't even his squeak left. We had bully beef camouflaged to look like haggis for New Years Day. 1917Jan./Feb. Things went along very well and we were getting famous as a counter battery. We would be shown a photograph of the next day's targets, and after we had shelled them, we were shown the results. In February the Germans fell so far back that all touch with them was lost for a couple of days. We were out of range so we were pulled out of the line for a weeks fest which we spent at TALMAS, not far from AMIENS. Needless to say a good time was had by all. By devious routes we eventually got the guns into position on the main road between ANZIN & MAROEUIL (not far from ARRAS). This was in No. 16 Sqdn's area. We spent a couple of weeks in French dug-outs but did not fire the guns. When we were completely lousy (which didn't take long) we moved up to NEUVILL ST. VAST, and immediately got into action preparing for the Vimy Ridge battle. It was in this position I was visited by Corporal Skidmore-Jones, I saw him twice.March/April When the offensive on Vimy Ridge started, the battery moved up to THELUS and after a few days of severe action, my dug-out was blown up and I was hurled across the road. Only suffering from bruises, the Major gave me the rest of the day off, and I went to the nearest village of ETRUN where I got really canned. May/June The Battery next moved to KEMMEL VILLAGE which soon proved to be a hot shop. Had my mast blown down 3 times in 2 days, and the guys and halyard looked like pieces of string instead of ropes. It was just about this time Lieut. Maddocks visited me, after I had spent 36 hours in a gas mask. Imagine what I felt like telling him when he said I should splice all the ropes and paint different colours around the mast. I was saved having to do all this nonsense by the Major who heard the instructions. He in no uncertain way told the Lieut. where to go, and not come bothering again. This battery position was too hot, so we had to pull the guns back behind KEMMEL HILL. There we continued to plaster the German guns just before the mines at MESSINES and WYTSCHAETE ridges went off. After the battle, the battery then pulled out and made north. We had a few weeks rest at POPERINGHE before taking up another position on the YPRES COMINESE Canal, just abreast of BEDFORD HOUSE. No. 121 Siege Battery, 9.2" Hows. were just below us, and below them at SPOIL BANK was another battery in which Alfred H. Lane served as an Operator. We had many excellent shoots from this position, but it got a decidedly hot one. It was here on the 25th June I was awarded the Military Medal. Towards the end of June we were completely wiped out, all of the guns were destroyed and the ammunition blown up. We suffered very heavy casualties, only 28 men left unwounded out of the total complement of the battery. I was wounded the next day and taken to the C.C. Station, after to Hospital at ETAPLES. July 1917 After about a month away I was back with No. 126 S. Battery amongst all new faces, we then had 6" Hows. and we continued to advance, but the weather was putrid. When we got to ZONNEBECKE I was told to go on leave, which I thoroughly enjoyed as I had been in France and Belgium for nearly 19 months. After leave I had to report back to ST. OMER where I did a turn of instructing. This was definitely a dead loss and a waste of time. I was then posted to a Squadron outside BAILLEUL where I met Sgt. Buchan? D.C.M. and Med. Militaire also Sgt. Sefton. I also met Corp. Nairn and others whose names I have forgotten. We had a cushy time here. Eventually I was sent to the 9th Corps H.Q. on the LOCRE road, why, don't ask. I never received a call. A Corporal Longley used to visit me, but when I saw him first, I thought he was an officer as he was certainly dressed like one. I even saluted him. I won't tell you what I told him when I found out he was only a lousy Corporal. After a couple of weeks the 9th Corps. went to Italy, and I nearly went with them. I was eventually stopped and told to report to No. 53 Squadron, RE. 8's at ABEELE. Lieut. E.T. Driver was the Wireless Officer, a short Canadian but a very nice chap. His Artillery boots nearly came up to his thighs. He said I had had enough of battery work and gave me the job of checking all the shoots as they were taking place. At times this job became really hectic, especially when about nine shoots were taking place at the same time. 1918Feb. 1918 Around mid February I left with the Squadron to go south, and after proceeding through the old Somme battlefield, through PERONNE, NOYON and HAM, we eventually arrived at VILLESELVE near LAON. Had a very comfortable stay here, plenty to eat and drink, and were able to have a bath when we liked at a place called BEINES. We did practically no work except take the press news, play football and generally dodge the column. There was a number of German bombers (Gothas) flying over us each night on their way to bomb Paris. We took no notice of them until one night one bomb must have accidentally dropped near us. We afterwards took notice of them and scampered like blazes on their approach. No. 53 Squadron left Abeele at 4.0 a.m. on 21st Feb. 1918 for a destination unknown. Arrived at Candas at 5.0 p.m. same day, feeling very fed up and thirsty. Left Candas at 7.0 a.m. on 22nd Feb and proceeded towards Peronne. We passed over a considerable portion of the Somme battlefield, and dead bodies were still lying about in goodly numbers, and of course the shell holes were there in abundance. We arrived intact, more or less, at Peronne, which place was in one hell of a mess and appeared to be surrounded by water. We rested there for the night and proceeded next day over country which had been ravaged by war, this part of France was the slice of ground from which the Germans retreated in Feb. 1917. It was most interesting for we Wireless Operators who had spent so much time on the Somme battlefield to see the various Battery positions where we spent so many "happy" days and lousy nights. We proceeded through Nostle, Noyon and Ham, and at all these places we were made very welcome, so much so, that the majority of us were Hors de Combat through inebriation. There was much speculation as to where we were going to make our Headquarters, some said Soissons or Laon to relieve the French, others thought we were making for Germany on our own. However we eventually arrived at a place named Villeselve, just north of Laon, where we took over from a French squadron which flew Caudrons. Naturally the whole camp was lousy. We erected a vie areil but although we had good signals, we were given to understand that no shoots would be attempted from this position. We spent our time taking press news, and playing football. We discovered a private house from which we could procure the nicest of egg and chips, you can bet your life we did ourselves well in this respect. In the afternoons we could go to a place called Beines where we could have a bath in a zinc tin, out in the open, and the Madam would bring us around towels whilst we were having our ablutions. After we had become wet outside, it was only reasonable to expect us to get wet inside, this we did with gusto. Occasionally in the evenings we would walk as far as Guiseard and be entertained by a Concert Party. (I am of the opinion that this Party became very famous later on at the London Music Halls). At all events all the items were extremely good. Villeselve was about 15,000 metre from the firing line and nothing of a very exciting nature took place. We had no bombs or shells, but every night a number of Gothas used to fly over us en route for Paris where their loads were dropped, the City apparently suffering heavily.Mar. 1918 The German offensive began around ST. QUENTIN and owing to their rapid advance the Squadron packed up and made for AMIENS. A couple of us were left behind to set fire to petrol, unflyable aircraft and other stores which could not be carried. Our instructions were to start the fires immediately we saw any Germans, we saw them, cavalry coming from BEAUMONT direction, up goes the fire and away we go like hell. We could not connect up with the Squadron so we made our own way to AMIENS, where we arrived a couple of days later after dodging the Germans from one village to another, the exact time and date was 8.30 p.m. 25th March. The town was in the middle of an air raid, and parts of it were burning furiously. We heard the Squadron had gone to FIENVILLE, we found them at last, but they were packing up to go to BOISENGHEM. We went with them. Here we had a cushy time just taking the press for the Officers and generally getting into trouble with the W.A.A.C's at NORTBECORT. My godfathers, couldn't those girls drink and fool around. We were very sorry to leave here (although, I think some of the chaps were glad). On the 11th March 1918 a Gotha was brought down by an S.E.5. On the 16th March we went to a picture house in Beaumont but apparently the lights went dud and we saw nothing. About this time there was a sudden scare about spies, and naturally everyone considered they had seen a person doing "Strange" things. However a couple of us were walking out one night near Beaumont and we spotted a lighted candle behind an uncovered window. We knocked at the door and upon receiving no answer, we smashed the window and put out the candle. We reported the address when we got back to the Squadron, and eventually got a bill for willful damage to the window. This of course curbed our enthusiasm for spies. Lieut. Driver, a Canadian was our Wireless Officer and he considered we had done right so he paid the bill for us. On the 21st March, the Germans attacked in strength and the Squadron packed up for Carligny, and in the packed up state, we were told to stand by. Squadron later moved off to Montdidier, which was afterwards altered to Bertangles, the actual movement was made 12 noon on 24th March in great haste as German Cavalry were seen patrolling near Beaumont. A few "Volunteers" (you, you and you) were told to stay behind to set alight to the petrol and surplus spares, and being one of the "yous" I certainly did not relish the job. The Squadron eventually went via Noyon, Roye Nestle to Amiens, this town was blazing fiercely owing to air raids, and instead of stopping at Amiens, the Squadron went on to Fienvillers. We who were left behind to do the "Firing" were told to set alight as soon as we saw any sign of the Germans. What we saw being done on the aerodrome was the digging of a lot of holes, waist deep, and Infantry Officers chasing around looking for machine gunners, of course that wasn't our war, and as soon as we saw the Germans, up goes the fire, much to the consternation of the Infantry, and off we skedaddled hell bent. We found the Germans were already in most of the Towns and villages, so we cut across country and were welcomed in quite a number of places with the sight of a barrel of champagne with the top open into which you tipped your tin hat and refreshed yourself. This party after a lot of minor adventures, arrived at Amiens, where we soon found ourselves soothing damsels in distress, in the various tunnels under the Railway Station. Here we found the Squadron had gone to Flanvilliers, after a lot of lorry jumping, we got back to the Squadron, where we were immediately put on guard. On the 26th March, or there about, the Squadron moved off to Boisenghem where a general sorting out was done as apparently a lot of strays had been picked up en route. April 4th The Squadron then went forwards to ABEELE. Around about the 8th April, the Germans launched a heavy attack south of ARMENTIERS, and made such a good progress that we were forced to pack up again. After a rush, we found ourselves at ST. MARIE CAPPEL, at the foot of CASSEL MOUNT, where we stayed exactly 1½ days, then we were off again to CLAIRMARMARIS FORET, about 2 miles from LE NIEPPE. The aeroplanes had to fly in fog, and to see the aerodrome next day when the fog cleared was enough to break one's heart. The planes had landed one on top of each other and there were numerous crashes and casualties. Here we had a real sort out, and a very necessary re-organisation. Operators Les Briggs, Chas. Tweedale, Alf Lane, Geo. Trott, Bill Fry and a host of others had found their way to No. 53 Squadron, so you can imagine what fun and games went on. Flogging revolvers for bottles of whisky with the Officers was one good game. Owing to night bombing, which at times was severe, all the personnel had to sleep in the forest each night and a number of civilians also went there for shelter, this combined with the whisky enabled us to have a thoroughly nice time. We were joined by a second Lieut. Broadley, a very nice chap, also a second Lieut. Owen came to the Squadron, why, nobody knew, he was a very timid sort of chap, and did not appear very popular with the Officers or the men. We stayed here until 4th April, when we packed up for Abeele again where we arrived next day. We remained here until about 11th April when owing to further German advances, we pulled out to Marie Capelle where we stayed one night, we afterwards shifted to Clairmaris Foret, near Le Nieppe, where we picked up quite a number of Wireless Operators, Les Briggs, Alf Lane, Idris Williams M.M. and quite a lot of others whose names I forget, when the German attack had slowed down and eventually brought to a halt, the British and French commenced counter attacking, and the Squadron was eventually sent to Abeele. As the Allies were making good headway, the Squadron then moved up to Seclin eventually finishing off at La Neffe after the Armistice. Mind you, I had a whale of a time whilst I was with this Squadron, all the chaps were exceptionally nice, and with the ups and downs, managed to make a very difficult period most enjoyable. May/June Practice shoots were arranged to enable the new observers to read maps correctly and give accurate positions of shell bursts. Our "bursts" consisted of a cigarette tin filled with gunpowder and fitted with a length of fuse. At an appropriate time this was placed in an arranged position and lit. Afterwards the Observers details were checked to see if the position corresponded. These fuses blew into strange places, one on the back of a reclining cow, didn't she shift. Another on the thatched roof of a cottage, luckily we put the fire out. There was a row in each case, but c'est le guerre. Another time to instruct the Observers regarding "unobserved" results, we threw the "burst" into a pond, and after a couple of seconds, nearly all the water blew out on to the bank, including hundreds of frogs. Then we saw a French farmer running towards us with a pitchfork ready to do us in. However we stood our ground. We argued as best way we could and found out this pond was a breeding ground for their National food, and during the argument, the frogs, which had only been stunned, began plopping into the pond until in the end there was nothing to argue about. We then accompanied the farmer to his cottage where we partook of coffee. July/August After a lot of strenuous work such as training Gunners to be Operators, Popham panel instructions etc. etc. we then moved to another position in ABEELE. It was while here I was told experiments were to be made with wireless telephony, and after a while I was picked out to start the experimenting. I was transported, together with a complete set consisting of Mark 3 tuner and 3 valve amplifier, spare batteries, mast etc. to the top of KEMMEL MOUNT, with a week's rations, the tinned variety and biscuits. The nearest troops to me were those in a lovely sheltered observation post about ½ mile away. It wasn't a very healthy spot to do any visiting. I think a success was made of the job. At all events, after the first shoot, my notes were collected and rushed back to H.Q. and quite a fuss made over them. I was not sorry when the week ended as I had become soft after such a long time away from the batteries and as the shelling on the top of KEMMEL MOUNT was severe, especially at night, it was nice to get back to ABEELE. Sept./Oct Things were getting better for the British Army and advances were being made and in due course the Squadron moved to near MENIN. We were joined by two RNVR operators, Corp. Buchan and L/seaman R. W. Shaw. At this place Operators Young and Holland were then instructed to take over Wireless Telephony. Nov. Packed up again and Squadron on the move to SVELGHEM, I went on leave on the 8th Nov. from this place. After a good leave, during which the Armistice was proclaimed, I returned to France, and after tracing the Squadron through COUTRAI and LILLE, I eventually caught up with them at SECLIN. Dec. We then moved on to LA NEFFE near CHARLEROI and just before Christmas I was transferred with L/seaman R. W. Shaw to "O" Flight at THY LE BAUDWIN. 1919Jan. 1919 Here we had a good time, chiefly playing football and having nightly trips to CHARLEROI. All things come to an end, and at last I had to report to GERPINNES where I was told I was to be demobilized. I eventually got on a train at CHARLEROI and proceeded to DUNKERQUE. We arrived at Folkstone about 4 p.m. (forgotten the date) boarded a train for Victoria Stn. After arrival there, we got on another train for Chistleton camp, arriving after midnight. There was no reception committee so we proceeded to wake up the camp, don't forget there was a whole trainload of troops for de-mob. Infantry, Artillery, in fact all kinds. We must of put the fear of heaven up the camp, because believe me, we were rushed from one hut to another, dropping something here, signing something there and after about an hour were left with a sandbag (this was given to us free) full of our personal belongings. We were now free men again so we walked to Swindon station and Freedom and a Country fit for Heroes. Strange though, nobody seemed to want us except our own kith and kin. |